Prior to visiting West Virginia University, I was unaware of the Immunology and Medical Microbiology (IMMB) major, which is only offered at a handful of institutions in the country. The curriculum piqued my interest, and I changed my major immediately after completing my “Discover WVU” session; I never looked back. What I found within the IMMB program was more than a unique major—it was home. I found faculty members and staff with immense knowledge and a passion for introducing me to the world of immunology and microbiology. Small classes with individual attention and instructors who knew my name was the norm.

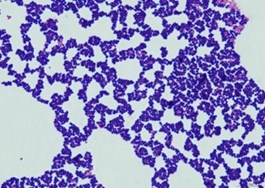

Within the first several weeks of class, we began learning how to isolate bacteria on media. As our understanding progressed, we were slowly introduced to more in-depth, microbiological explanations and learned the characteristics of different bacteria. Our first test, the Gram Stain, allowed us to examine bacteria under the microscope to determine if it was gram-positive or gram-negative (an indication of the thickness of peptidoglycan that makes up the bacterial cell wall), if it was bacillus, coccus, or spirilla (denoting rod-shaped, circular, or spiral cell shape), and its formation pattern (staphylo- form clusters and strepto- form chains). For example, the image to the right is a gram-positive staphylococcus.

Within the first several weeks of class, we began learning how to isolate bacteria on media. As our understanding progressed, we were slowly introduced to more in-depth, microbiological explanations and learned the characteristics of different bacteria. Our first test, the Gram Stain, allowed us to examine bacteria under the microscope to determine if it was gram-positive or gram-negative (an indication of the thickness of peptidoglycan that makes up the bacterial cell wall), if it was bacillus, coccus, or spirilla (denoting rod-shaped, circular, or spiral cell shape), and its formation pattern (staphylo- form clusters and strepto- form chains). For example, the image to the right is a gram-positive staphylococcus.

Eventually, we managed to perfect a multitude of tests to collectively allow the determination of an unknown bacteria: our final project in IMMB 150. The basic tests such as catalase production, oxidase production, glucose fermentation, and motility allowed us to place organisms into broad categories for downstream tests.

Then, differential tests were performed to select for certain groups of organisms and reveal differences among sugar fermentation, acid production, and hemolysis. Examples of these tests are featured below. The left image depicts glucose fermentation with gas production (yellow) compared to no glucose production (orange). In the middle, the motility test confirmed that the organism is highly motile, indicating the presence of flagella, which are especially useful in determining the unknown. The right image features a type of differential media, Hektoen Enteric agar, which further distinguishes between organisms.

Then, differential tests were performed to select for certain groups of organisms and reveal differences among sugar fermentation, acid production, and hemolysis. Examples of these tests are featured below. The left image depicts glucose fermentation with gas production (yellow) compared to no glucose production (orange). In the middle, the motility test confirmed that the organism is highly motile, indicating the presence of flagella, which are especially useful in determining the unknown. The right image features a type of differential media, Hektoen Enteric agar, which further distinguishes between organisms.

While very useful in understanding the characteristics of an organism, these tests are time-consuming and unrealistic for large-scale or commercial use. Thankfully, rapid biochemical tests have been designed that allow for a series of wells to be inoculated with the bacteria and scored according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The results create a numerical code that can be entered into an online database that reveals the genus and species, as well as additional test suggestions.

As complicated as this might seem, I acquired all of this knowledge in one semester. Having no microbiology background from high school, I was worried that I would straggle behind my peers without a grasp of the concepts. However, this was not the case. To any prospective IMMB student who doubts his or her ability, know that you are in good hands, you will learn, and you will overcome the preconceived obstacles you have placed before you.

If the Coronavirus has done one thing positive, it is underscoring the criticality of emerging immunological disciplines. I implore anyone seeking a greater understanding of the body’s immune system, a unique preparatory route for medical school, or even a pathway to the pharmaceutical industry to explore IMMB.

Feel free to reach out to me should you have any questions. I would love to discuss this further with you!

Email: msh0036@mix.wvu.edu

Instagram: @matthew.hudson