Paul Chantler

“One of the biggest thrills I get is to mentor students all the way through and see them eventually become better than I am.”

Soccer player turned scientist mentors research students

Paul Chantler was always fascinated by Exercise and science. At the age of 16 and a native of Liverpool, England, he was the second fastest sprinter in Great Britain and played soccer for Everton FC. When he began his studies in college, he was intrigued by the cardiovascular system which paved the way for a remarkable turnaround in his journey.

He pursued his undergraduate degree at Liverpool John Moores University where he earned a bachelor’s degree in Sports and Exercise Sciences , followed by a doctorate degree in Exercise Physiology with a specific emphasis on cardiovascular physiology.

Once he graduated, Dr. Chantler poured his tenaciousness into research. He moved to the United States in 2005 starting a post-doctoral fellowship in the National Institute on Aging (NIA) in Baltimore, Maryland. Four years later, he joined West Virginia University as an assistant professor in the Exercise Physiology Division.

“It seemed like a wonderful opportunity for many reasons,” Dr. Chantler said. “At that time, there weren’t that many professors at WVU doing human research, rather more basic scientists in the Exercise Physiology division. So, that gave me a niche and fostered a collaborative environment in translational research. Living in West Virginia was another major draw because my wife is from the east coast, so it was a great in a positional sense.”

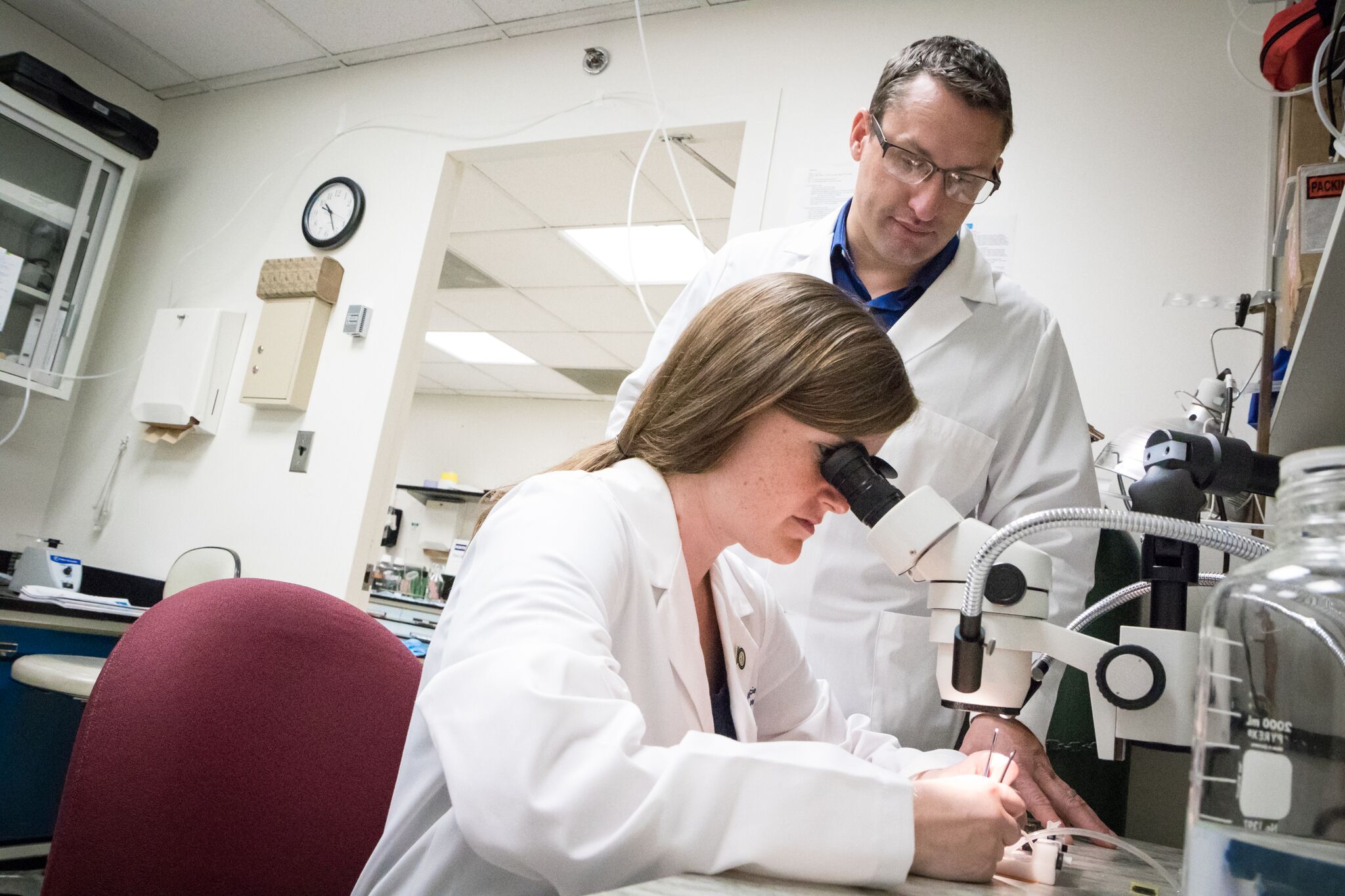

Today, in his capacity as an associate professor, Dr. Chantler assumes multiple roles. He teaches undergraduate and graduate students in the Exercise Physiology division, runs a lab where he constantly develops his research toolkit through various projects, co-directs the clinical and translational sciences Ph.D. program and is a member of different committees across the health sciences disciplines. To him, one of his biggest achievements is paving the way for a new generation of scientists. He explains how being a mentor entails some key features, from being flexible and understanding, to empowering the students, giving them the confidence they need, enriching their scientific learning, and presenting opportunities for them to blossom.“I have two masters’ students and two doctoral students in my lab, all doing exceptionally well and graduating soon,” he said. “One of the biggest thrills I get is to mentor students all the way through and see them eventually become better than I am.”

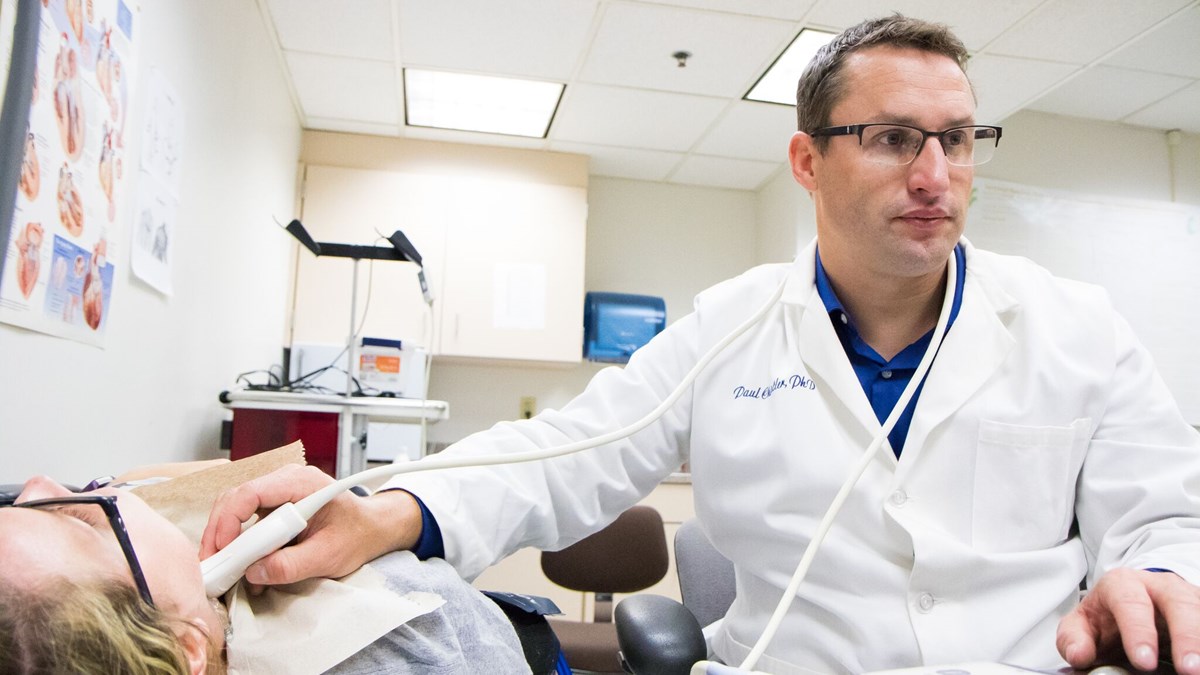

Coming from a human clinical research setting, Dr. Chantler wanted to espouse his background to the basic science aspect of research. When he came to WVU in 2009, he established a human cardiovascular lab and a human performance lab where research was focused on aging. His research projects are particularly significant to Appalachia. His lab’s primary focus centers around examining how various lifestyle interventions can be incorporated into a high cardiovascular disease risk community in Appalachia with the goal of directly improving the cardiovascular health of individuals.

“Along with a lively group of my graduate students, we have taken our research on the road,” Dr. Chantler said. “We had a big success in Spencer, West Virginia, where we partnered with local community people in a rural health family clinic and performed a pilot study. Over the course of 10 weeks, multiple lifestyle interventions were performed and cardiovascular assessments were conducted, both prior and following the interventions.”

Collaborations have always represented a significant part of Dr. Chantler’s work and channeled into his research projects. Throughout his eight-year career at WVU, he collaborated with vascular biologists like Jefferson Frisbee, Ph.D. who is now in Canada, and Mark Olfert, Ph.D., as well as professors in the Physiology, Pharmacology and Neurosciences department like Tim Nurkiewicz, Ph.D.

Another area of interest for Dr. Chantler is stroke. He was one of the investigators included in the stroke CoBRE with James Simpkins, Ph.D., a large federal grant provided to WVU to help train junior investigators as the team researches ways to mitigate the devastating effects of stroke.

For those considering research as a potential career avenue, Dr. Chantler reiterates that it is not a typical nine to five job. It can be challenging and repetitive, yet it allows one a great deal of flexibility and a rewarding sense of accomplishment especially when the data comes together and potentially leads to a contribution to science or even a breakthrough.

In an attempt to further clarify some of the misconceptions surrounding the field, Dr. Chantler shares some key pieces of advice.

“I don’t think research is any more or less stressful than other jobs, you just have to develop the skills to cope with stress and surround yourself with a good support system,” he said. “As a researcher, you submit numerous papers and grants, and they constantly get reviewed and sometimes rejected. The only way to move forward is by bouncing back. Thus, growing a thick skin becomes vital for survival. Eventually, with dedication, hard work, and perseverance, the challenges and hurdles become the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Dr. Chantler credits his self-driven motivational skills and determination with the accomplishments and the breadth of experiences he has acquired to date. He is married with two children, and says his favorite hobby is playing soccer.

“If I wasn’t going to be a scientist, I would have been a football player,” he said.